Life is not measured by the breaths you take, but by the moments that take your breath away. - unknown

I awakened and sprang off the couch like a kid leaping out of bed on Christmas morning. It was 6:00am Alaska time and the skies were clear and bright blue. In the grand scheme of things, this was just another days riding on a crappy road. I kept trying to convince myself that as I got dressed. I never managed to though. I was stoked and like that kid at Christmas bolting to the tree to see what Santa left, I bolted out to Hester to see what Alaska had in store for me. Hester's dirty appearance was misleading. She was fully fueled and had fresh tires and brake pads. She had run like a top on the entire trip. I've ridden long and hard for a week straight and she's hung in there. My Gold wing riding friends can try to convince me of their machines' superior reliability after they make their trip to Alaska and back. And BACK. Hmmm...I hope I don't have to eat those words. I digress...

My friend Jeff let me leave some of my gear in his corporate apartment. I unloaded my spare clothes and a few other items, taking only a few tools, some water, and my camping gear. A lighter load could only make the ride easier. I mounted up and headed north on the Elliott Highway. The Dalton Highway begins about 70 miles north of Fairbanks near a town called Livengood. I chuckled to myself when I considered that I was certainly livin' pretty good the last week.

The weather was perfect with a light breeze, crystal clear skies, and temperatures in the low 70's. Still, I wore my chaps, a full leather jacket, and my Shark Evoline modular helmet. I had been advised that the trucks on the Dalton are notorious for throwing rocks and other debris. I had come too far to take senseless chances. I also knew that despite the extended daylight, the temperature up here still drops significantly during the late hours. The Elliott Highway provided a nice primer for what was to come. Fully paved with sweeping, banked turns, and surrounded nearby by trees and by mountains at a distance, the Elliott allowed me to settle in to a riding groove. I was in the final chapters of my "Pillars of the Earth" audiobook and was anxious to reach the end of that adventure as well. When it ended, I queued up my Rush playlist. As the opening riffs of "The Spirit of Radio" blasted forth, I grabbed a handful of throttle, stretched my legs out on my highway pegs, took a deep breath, and rocketed north.

The Elliott Highway gives way to the Dalton highway with no fanfare; not even an intersection. There's just a sign. I stopped there to put on my CB radio and an orange vest. The truckers are notorious taking up the entire road and I wanted a means of reaching them and to be as visible as possible. I was advised to use channel 19 to announce my presence at blind turns and on the roller coaster hills. The Midland radio I used was small and clipped to my vest. It had an ear bud and a voice-activated throat mic. At one point, I forgot about the voice activation feature, but was promptly reminded of it by a trucker who had grown tired of hearing me sing along with Rush.

For some reason, I expected the road to turn to shit as soon as I was on the Dalton. I was pleasantly surprised. The first hour or so on the Dalton was as fast and smooth as the Elliott had been, although that would certainly change shortly. Hazards abound on the Haul Road. I saw more moose and sheep than anything. It was common to come around a corner and find either a pile of rocks or an animal sitting there. I believe the most nerve racking part of the Dalton was the unknown. I found myself holding a such death grip on the handlebars that my forearms went numb all the way to my elbows. I had to force myself to relax and realize that Hester had this.. It was going to be alright.

After a while the Trans-Alaskan Oil Pipeline came into a pretty regular view. There are several cut-outs along the Dalton with roads leading to the pipeline. They're gated to keep vehicles out, but a person can just walk through them. I've seen images and video footage of the pipeline, but nothing beats getting a first hand look. Under construction from 1974 to 1977, the pipeline spans 800 miles from Prudhoe Bay to Valdez and crosses three major mountain ranges along the way. Over 420 miles of the structure lies above ground on specially engineered flexible trestles. I read that this is to prevent pipe temperatures warmed by the hot oil from melting the permafrost and wreaking environmental havoc in the Alaskan ecosystem.

There are several sections that were constructed along known wildlife migration paths and as such were built extra high to allow wildlife to pass under it. When the first oil production started flowing through the pipeline, it took three weeks for it to reach Valdez from Prudhoe Bay. It was an engineering marvel, built under the harshest conditions, and was designed to last twenty years. When I considered the fact that it's 34 years old now I wondered briefly how well it's holding up. This pipeline is a testament to how man can engineer and oversee a solution which can exist in harmony with nature and still serve the purpose for which it was designed; even with 1970's technology. It really negates the eco-Nazi argument that we can't safely extract oil from the ANWR.

Eventually, the road winded down to the mighty Yukon river and the famous 1/2 mile long bridge that traverses it. I motored slowly across the wooden planks and took in as much of the scenery as I could. I was awestruck by the structure and by the river it spanned. I stared at it in my mirrors as I made a sweeping left hand corner and was so distracted by the sight that I rode right past the only available fuel stop for the the next 180 miles.

|

| Hot Spot Cafe Dining Room |

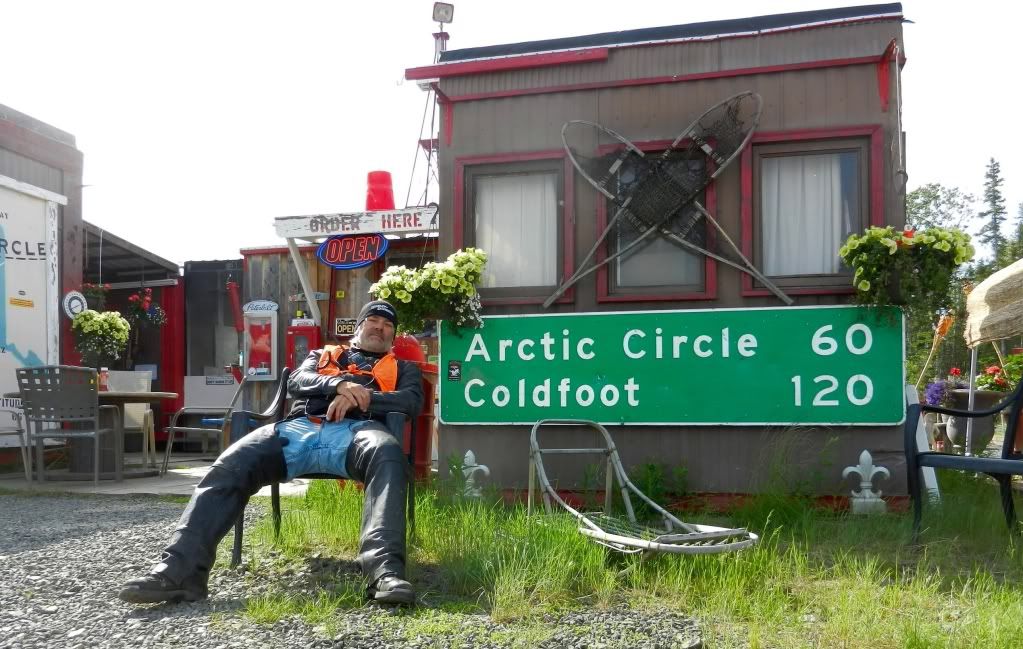

Before I knew it, I saw a sigh for the Hot Spot Cafe. I had read about the Hot Spot and knew that I wanted to stop there. You can't say you did the Dalton if you don't stop at the Hot Spot Cafe. I rode up and saw that Hester was the only vehicle there; well, the only running vehicle. The place was run by a pale-skinned woman wearing a turban and who had no eyebrows. She was congenial, but spoke with the raspy voice of a chain smoker. One might think that a person living in this tiny box in the middle of nowhere might be excited to see people. One would think otherwise after a visit to the Hot Spot. Lack of congeniality notwithstanding, the woman cooked a great burger. The Hot Spot also offers a plethora of souvenirs ranging from shirts, bottle coozies, and even a book titles "Sex in a Tent". I was curious, but didn't look. I could have spent hours just wandering around the place looking at all the crap laying around. I reminded myself that I had an agenda and needed to gas up and head further north. I asked where the gas pumps were and the woman just stared at me. It was then that I learned that I had motored past the last fuel stop before Coldfoot a few miles back at the Yukon River Bridge. I did the math. I had just over a half tank of gas and I carried a spare one gallon can in my right saddle bag. I knew that five gallons at 40 miles per should get me to Coldfoot. I was petty sure I could make it. Then, I considered the fact that the gas up here is low 87 octane and remembered that Hester's mileage drops considerably on low octane fuel. The bridge was only about four miles away. Common sense got the best of me and I decided to backtrack to the bridge for fuel. I was in no hurry and I had plenty of daylight. Better safe than sorry; especially out here. I paid for my lunch and as I was mounting up, was asked by a trucker who had stopped in "You going up or down?". I replied that I was going up, to which he replied "On THAT? You're outta your mind": I thought for a second and said "If I were going down, then I would have already made it up...on THIS; so what's your point?" Apparently, he didn't have a point because he didn't answer.

|

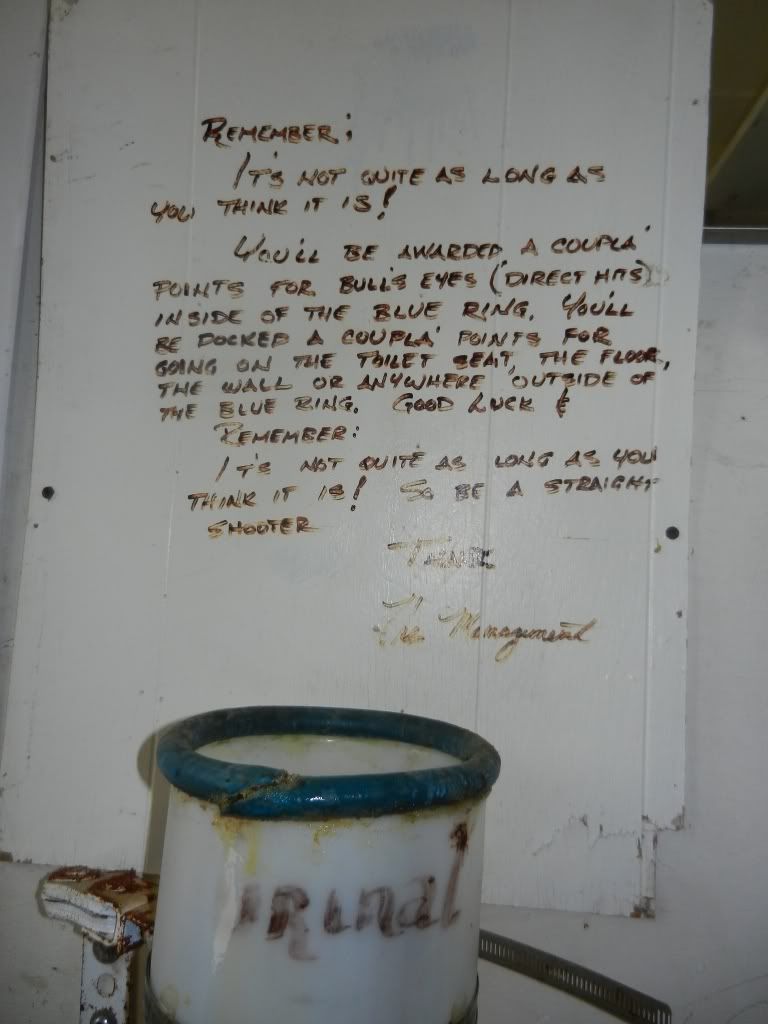

| Sign Outside Hot Spot Bathroom |

|

| Sign Inside Hot Spot Bathroom |

|

| Yukon River Bridge Gas Stop |

I rode off and backtracked the three or four miles to to the Yukon River Bridge. At $5.55 per gallon, gas there was the highest I've paid on the trip. I filled Hester's tank and took off again knowing that my next stop would be at the Arctic Circle. Shortly after the gas stop, I heard traffic on my CB radio. I couldn't quite make it all out, but I did hear the words "roller coaster" in the transmission. Before I knew it, I was at the roller coaster hill. This was the steepest and tallest hill I've ever ridden. As you approach it and start the descent, it's just like a roller coaster in that you can't see beyond the bend to view the road all the way to the bottom. I found myself standing on the foot boards in a failed attempt to see the bottom. I spoke up "Motorcycle northbound into the roller coaster" hoping my CB transmission would be received by any vehicles heading my way. To my surprise, I got an answer. A state worker in a pilot vehicle was sitting at the top of the other side of the hill waiting on the trailer she was escorting to arrive. "You're clear, but don't stop in the bottom" was all I heard. I blasted into the depth and yelled "Woooo hoooooo!!!" all the way down. "Kinda fun isn't it?" I heard in my earpiece. Shit! I forgot about the throat mic again. I grabbed a handful of throttle and raced back up the other side. The ascent out wasn't as steep as the descent was, but I was well aware that it would be on my way back down to Fairbanks. Other super steep hills followed, but they paled by comparison to that first one. The next interesting corner was an off camber steep uphill climb on a gravel covered surface. The challenge was to maintain enough speed to climb the hill, but not go so fast as to lose traction in the loose gravel. Add the off camber aspect to the mix and you'll understand why they call one of these spots "Oh Shit Corner".

I rode off and backtracked the three or four miles to to the Yukon River Bridge. At $5.55 per gallon, gas there was the highest I've paid on the trip. I filled Hester's tank and took off again knowing that my next stop would be at the Arctic Circle. Shortly after the gas stop, I heard traffic on my CB radio. I couldn't quite make it all out, but I did hear the words "roller coaster" in the transmission. Before I knew it, I was at the roller coaster hill. This was the steepest and tallest hill I've ever ridden. As you approach it and start the descent, it's just like a roller coaster in that you can't see beyond the bend to view the road all the way to the bottom. I found myself standing on the foot boards in a failed attempt to see the bottom. I spoke up "Motorcycle northbound into the roller coaster" hoping my CB transmission would be received by any vehicles heading my way. To my surprise, I got an answer. A state worker in a pilot vehicle was sitting at the top of the other side of the hill waiting on the trailer she was escorting to arrive. "You're clear, but don't stop in the bottom" was all I heard. I blasted into the depth and yelled "Woooo hoooooo!!!" all the way down. "Kinda fun isn't it?" I heard in my earpiece. Shit! I forgot about the throat mic again. I grabbed a handful of throttle and raced back up the other side. The ascent out wasn't as steep as the descent was, but I was well aware that it would be on my way back down to Fairbanks. Other super steep hills followed, but they paled by comparison to that first one. The next interesting corner was an off camber steep uphill climb on a gravel covered surface. The challenge was to maintain enough speed to climb the hill, but not go so fast as to lose traction in the loose gravel. Add the off camber aspect to the mix and you'll understand why they call one of these spots "Oh Shit Corner".I rode on through the multitude of terrain and surface changes. It's strange. The Dalton has many stretches of perfectly maintained two lane highway. Then, it instantly changes to loose gravel over almost impossible to see (until it's too late) ruts and potholes. Then, there were stretches of dirt that were under construction and had been groomed by road graders. The grooves forced me to ride fast in order to stay vertical. Both the front and back wheels were fishtailing wildly. All I could do was hang on, stay alert for holes and rocks, and hope my inertia carried me through. I was reminded of the road from Destruction Bay a few days prior, but at least the Dalton was dry. Another hazard of the Dalton Highway is the truckers. They transport everything from oil to heavy machinery between Deadhorse and the rest of the world. When a truck passed by in the opposite direction, it wasn't so bad if I happened to be on one of the few paved surface sections. But when they approached and passed me in the slop, it's all I could do to hang on and maintain control. I learned quickly to approach the top of every blind hill from the far right because if a truck was approaching, they would undoubtedly be smack dab in the middle of the road, if not in my lane. The Dalton is there for the truckers and for the most part, the truckers see motorcycles as a nuisance.

About two miles from the Arctic Circle turnout, I came upon two Honda Gold Wing trikes parked on what there was of a shoulder. One of them was missing a rear wheel. The driver had hit a pothole that ripped the wheel right off the axle. I pulled over and asked if they had been able to reach help. They had not. I tried my CB radio; nothing. So I used my Spot Connect to send a message to their emergency contact. It took a few minutes and I had no way to know if they received it, but judging from the responses I've received from the other messages I've sent to the Alaskapade readers, I felt confident that someone would know. I left them a liter of water and headed on up the Dalton.

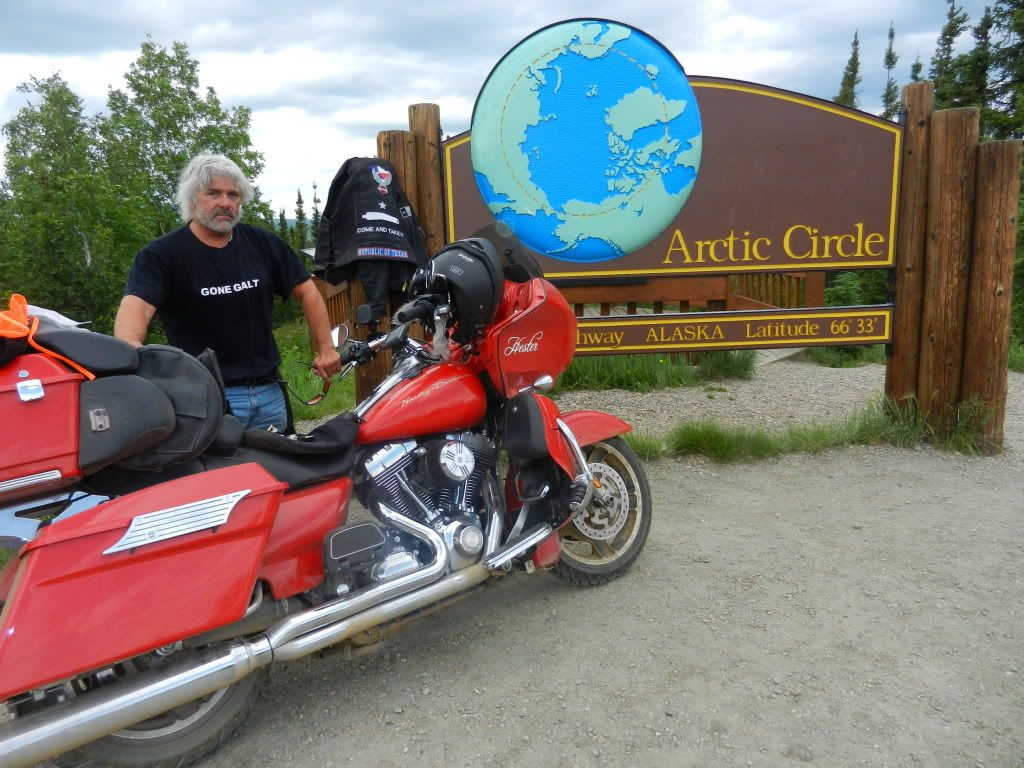

I knew it was only two miles to the Circle. My heart was pounding and even under my leather, I could feel the hairs on my arms and neck bristling like a Rhodesian Ridgeback who just heard a strange noise in the middle of the night. Then I saw the sign. I slowed to a stop, snapped a quick picture, and then drew a large breath. The turnout was another off camber, uphill chunky gravel road that curved to the left. I rounded the corner and about 1/4 mile later saw it. Five years of dreaming, eight months of planning, and 4,300 miles had all come to this. I rode into the parking lot, dismounted and literally ran up to the sign and slapped it with both hands. I couldn't believe I was really there. I felt a sense of accomplishment like never before. I haven't felt so happy since my sons were born. I have to admit that it was a pretty emotional experience. I thought of the people who told me I shouldn't do this; I couldn't do this; I wouldn't do this. I thought of Jeff who gave me a comfortable place to sleep and a base of to ride from in Alaska, of Hermann and Joeann's hospitality back in Jasper, and of Jim from Harley Davidson Forums who gave me so much advice from his experience. But mostly I thought of my friend Martin.

Marty and I worked together years ago and we both bought our Harleys about the same time. We were pretty much the same age and were in similar places in our lives. We both had grown kids, a little money and time to actually try to pull something like this off. We talked about this trip several times and every year something came up. Life always got in the way. I remembered how I was stunned when I learned about his untimely death and how I decided after his funeral that I was going. We had let life get in the way until death took his dream away. I remembered telling his widow that I was going and wanted to bring something of Marty's with me. Then I remembered his hat that she sent me. I took the hat out of my saddle bag, put it on, and just sat back for a while taking it all in. While I sat, a tourist bus drove in and unloaded a small crowd of people. The driver took a piece of carpet with dotted line on it and laid it in front of the sign and the passengers walked "across the line" and took pictures. It was kinda hokey, but enjoyed seeing the people having a good time. I had allowed myself to get a bit bummed out thinking about Martin and joking with the tourists was fun. One old lady asked the driver "How did that motorcycle get up here?" An old man came up to me, said he was an retired EMS worker, and then proceeded to tell me about all the motorcycle fatalities he worked over the years. After a few minutes, the bus departed and I was once again left alone with Hester and my thoughts. I took Martin's hat and placed it atop one of the posts on the Arctic Circle sign. Then, I set up a tripod and took a few pictures. I had accomplished all I planned. I made it to the Circle and I kept my promise to Martin's widow to bring something of his with me. Still, I couldn't bring myself to leave. I just moved Hester across the parking lot and hung out there a while.

|

| Christian & Shrug at Coldfoot Camp |

After an hour or so, I decided to take off. I was happy and my heart was full. I was also a hell of a long way from home! I rode back down the hill to the Dalton and had to make a decision. Do I turn right and try to go to Deadhorse or should I turn left and just go back to Fairbanks? I turned right. The way I saw it, I would never be here again and this was most likely my only chance to go that far north. I headed north another 60 miles to Coldfoot Camp and pulled in for gas. I pulled in front of the restaurant and was excited to see Christian and Mustang Joe. He was on his way back down from Deadhorse. He told me it was very cold, but the roads were not too much worse. It was only 200 miles further and I was convinced I could make it. Christian and I ate dinner and talked to the others visiting. I met people from Texas and a doctor who is a physician at a hospital in Chicago where I designed and deployed a wireless network. Desolate places like Coldfoot can still make the world seem small. I was getting ready to leave when a few trucks drove in and emptied out a bunch of oil workers from Prudhoe Bay. They were heading south because the weather in the north slope was turning. They all advised that I not try to make it because it would be too cold and wet to camp and there were no typically no hotel rooms available when the weather is bad. My decision had been made for me. I was heading south. Christian and I rode the route together and took turns leading. The ride back was more relaxing than the ride up. I suppose it was because I knew what to expect. Maybe I was more relaxed with the tension of making it to the Circle behind me. About halfway back to Fairbanks, we passed a tow truck with the broken Honda trike. I thought to myself, there's an expensive tow.

As I sat up there, i was amazed at the enormous expanse of nothing out there was; miles and miles of land, trees, streams, and mountains; all unspoiled by human “improvement”. I believe as the years pass, it's easy to grow full of ourselves and marvel at our own accomplishments, abilities, and our possessions. I gotta tell you though, those things quickly become less significant out there. A ride like this through this sort of majestic scenery does many things to a man. It makes your butt sore. It makes your hands go numb. Some of the road conditions will make the fillings in your teeth rattle. Still, the most profound effect on me was the sense of humility and insignificance I felt in the presence of all I could see. These mountains were here eons before I rode by them and they will be for eons after I go home. And regardless of what I might think of myself, I know my affect on them is nothing. I know also that their affect on me will last a lifetime.

The adventure continues tomorrow as I begin my ride home. I'll backtrack along the ALCAN and turn south to Prince George and make my way to Seattle. From there, I plan to ride across the top of the country and tour the Black Hills before turning south to Texas.